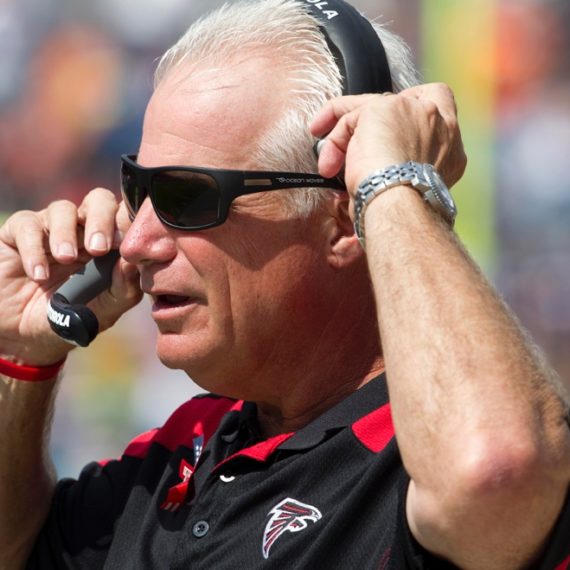

08 Feb His Name Was Carter. His Dream Was a Railroad.

George L. Carter had a vision for a railroad

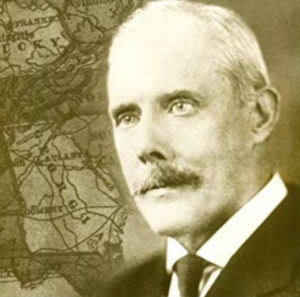

Labeled as the last great empire builder of America’s industrial revolution, George Carter shied from publicity, unlike the Carnegies, Vanderbilts, and Fords of the era, focusing instead on his big ideas. His biggest was a railroad whose headquarters were to be in a small town called Erwin.

The Virginia-born Carter was a self-educated entrepreneur who by age 18 was the general manager of a sprawling Southwest Virginia pig iron mining business. His vision was for creating new economies in the expanse of a largely unknown territory between Northern Kentucky to the Carolinas whose mountainous geography deterred from large industrial development.

Natural resources, such as coal in the late 1800’s, was plentiful and of high quality. Thus, Carter bought up 350,000 acres in Southwest Virginia but was plagued by small stretches of unconnected railroads. In fact, no one had been up to the challenge of building a single rail system that could connect Midwestern Cities such as Cincinnati and Chicago with the seaports of Charleston SC and Savannah GA where energy-hungry Europe could be fed coal instead of cotton after the Civil War.

Carter first settled in border town Bristol TN/VA as headquarters for his coal business. Even though he elevated the city in multiple ways, native residents frequently opposed the shy outsider. Out of frustration, he bought 8,000 acres around Kingsport, TN, where he first envisioned a home for his railroad company. He hired famous architects to build what’s known as the “Model City” and a brick company to build it, which today is General Shale Brick Company. He recruited Eastman Kodak to build a plant there, then soured of Kingsport, choosing Johnson City for his home for a railroad.

Artist Simon Winegar’s depiction of Clinchfield’s most beloved engines, Clinchfield #1.

Carter built a residential neighborhood for his future rail workers, today known as the “Tree Streets”; a flour mill to feed them, known as the “Model Mill” where it’s Red Band Flour grew to national notoriety, and a post office that became a courthouse on Ashe Street there. Opponents in the city then made his attention turn to Erwin as the railroad’s new home. The land he had envisioned for his railroad in Johnson City would instead be donated so that the State of Tennessee would create today’s East Tennessee State University that was founded in 1911.

Carter’s Carolina, Clinchfield and Ohio Railway emblem.

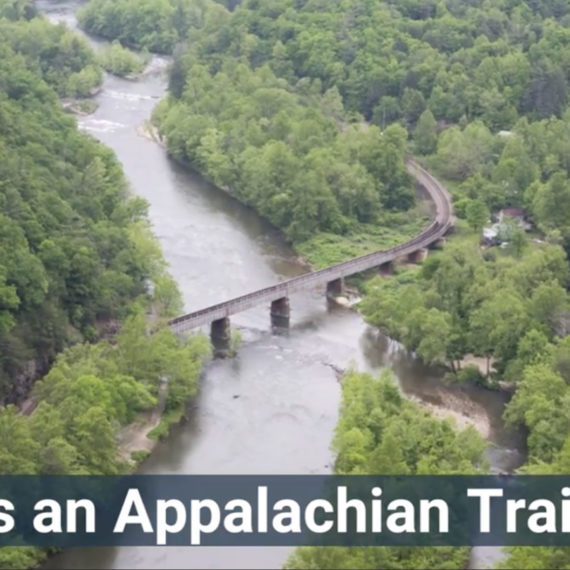

What would become the last Class 1 railroad built east of the Rocky Mountains would have its headquarters in Erwin. His rail line would connect the coalfields of Virginia and Kentucky and connect with the coal-burning textile mills of South Carolina, then link up to carry his coal to Charleston, SC, and a new coal port in Wilmington, NC. Spanning 266 miles across the Blue Ridge Mountains, the construction became the most expensive, by mile, rail project in history.

Carter’s passion for quality paid off in fewer time, life, and profit sapping derailments, opting for steel trestles instead of wood, and building tunnels through mountains rather than going around them. Hiring Italian stone masons and tunnel builders, his tunnels remain as a symbol of quality today. Initially begun in 1886, Carter saw the Carolina, Clinchfield & Ohio Railway chartered in 1908. The next year, Carter rode aboard the very first arrival of one of his trains into Spartanburg, SC’s Union Station the next year.

The new system could transport coal faster, better, and cheaper than ever before, and Carter’s commitment to his workforce gained benefit to Erwin. Beyond employment, Carter funded New York architect and community planner, Grosvernor Atterbury, known for his garden-city planning genius (he designed Forest Hills in New York City), to create a residential area including schools, industries, parks, and employee housing. Today, his vision still thrives along Erwin’s famed residential streets such as Elm, Love, and Ohio Avenue.

Carter died in 1936 in his hometown of Hillsville, VA, and after the passing of his wife, all of his remembrances, notes, photos and achievements were burned by his son, at the direction of his father, at the gravesite because Carter never wanted to be famous, just productive. At ETSU, the George L. Carter Railroad Museum is one of only a handful of locations that bears his name.

The Clinchfield Headquarters building remains near downtown Erwin.

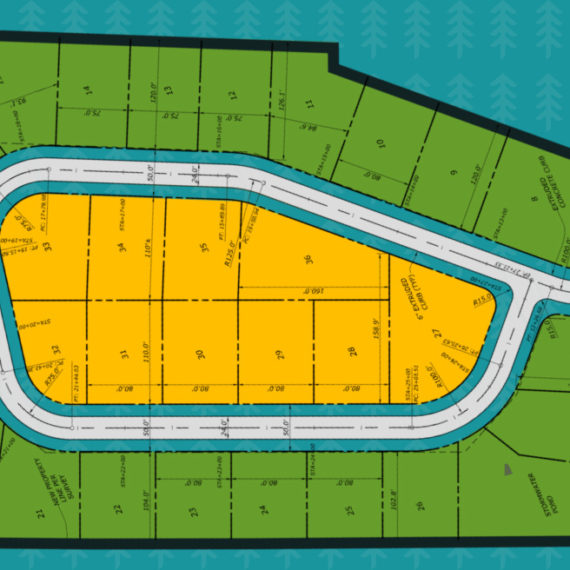

His beloved Clinchfield was later sold to today CSX railroad and after the Obama Administration called for the coal industry to be killed off, CSX closed the rail yards that today offer more than 160 acres for development. The Clinchfield’s Headquarters remains as a three-story monument and its passenger depot in town became the Unicoi County Library. The town offers the Clinchfield Railroad Museum for visitors. Yet, the families of Unicoi County still remember the buzz of a busy railroad town whose stories will be carried on through generations.